You're Not Building an ‘AI Product’.

Why model performance is a design constraint, and calibration is the real AI skill.

You’re an ecommerce app. You have an AI model that predicts which customers will cancel their order before it ships. Three scenarios: the model has 99% precision, 80% precision, or 40% precision. What do you build with each?

Precision means: when the model flags someone, it’s right that percentage of the time.

Most people answer like this:

99%: “Automate it, cancel their order before they do.”

80%: “Good start, but let’s improve the model before we ship.”

40%: “Not useful. Too many false positives.”

Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.

The right answer reveals the skill that actually matters when you’re building with AI. Almost nobody has it.

The Answer

Notify the customer: “Confirm or cancel your order”. Same model. Same email. Different intensity.

99% precision: Aggressive CTA. “Still want this? Click to confirm or we’ll cancel your order.” You’re almost certain they’ll cancel, better they do it now than you ship it and eat the return costs.

80% precision: Medium CTA. “Your order ships tomorrow!” with a visible, easy cancel button. You’re right 4 out of 5 times. Give them a clear out. The 1 in 5 who weren’t going to cancel? Most of them feel informed. No harm done.

40% precision: Soft CTA. “Your order is on the way!” with a subtle cancel link. You’re wrong more often than you’re right, but you’ve still got a meaningful signal over random. You can’t push hard. But you can quietly surface the option for those who need it.

One model. Three scenarios. Three calibrations.

The precision is the constraint. The intervention intensity is the variable.

This is the entire game. And most builders don’t even know they’re playing it.

The Skill Nobody Teaches

Most builders ask: Is the model good enough?

The rare ones ask: Good enough for what?

That’s the skill gap. Not “how do I handle uncertainty.” But “how do I calibrate the product to the confidence level I actually have?”

Netflix understood this early. Their recommendation algorithm doesn’t need to be right, it needs to surface options you’ll scroll past if they’re wrong. 80% of Netflix watch time comes from recommendations. Not because they’re perfectly accurate, but because the cost of a bad recommendation is close to zero. You see a title you don’t want. You scroll. You pick something else. Maybe you hover, decide not to click, move on. The algorithm watches all of it: the hovers, the skips, the half-watched episodes, and learns. Netflix has said this saves them an estimated $1 billion per year in reduced churn. Not by being right. By making “wrong” cheap.

Spotify understood this. Discover Weekly gives you 30 songs you’ve never heard. Some you’ll hate. But the product isn’t “songs you’ll love.” It’s “songs you might love.” The intervention is calibrated perfectly: skipping costs 30 seconds and a thumb tap. No wasted money. No broken workflow. No angry customer. And your skips train the algorithm just as much as your saves do. Failure is feedback. The product gets better specifically because it’s allowed to be wrong.

GitHub Copilot understood this at a deeper level. Roughly 30% suggestion acceptance rate. Think about that. Most suggestions are wrong. Seven out of ten lines Copilot writes are rejected. By any traditional software metric, that’s a broken feature. But Copilot is one of the fastest-growing developer tools in history. Why? Because a wrong suggestion costs you nothing. Gray text appears, you keep typing, it vanishes. A right suggestion saves you minutes. Tab to accept, keep typing to reject. 88% of accepted code stays in the codebase. Users report coding 55% faster. The product works because failure is free, not in spite of its error rate.

The pattern is consistent across all three. Winners don’t wait for perfect precision. They calibrate the intervention to the confidence they have. They design the product around the error rate, not despite it.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

Air Canada didn’t understand this.

Their chatbot gave a customer wrong information about bereavement fares. The customer relied on it, booked a flight, and applied for the discount. Air Canada refused the refund, then argued in a tribunal that the chatbot was “a separate legal entity responsible for its own actions.”

The tribunal called this a “remarkable submission.” Ordered Air Canada to pay $650. The chatbot was pulled from the website.

The product failed because nobody asked “what’s our precision, and what intervention is appropriate for that precision?” A chatbot that gives direct answers acts like a 99% precision product. Air Canada didn’t have 99% precision. They had a confident-sounding model and no fallback.

McDonald’s made the same mistake differently. They spent years building an AI drive-thru system with IBM. It misinterpreted orders, adding bacon to ice cream, ringing up 260 chicken nuggets. Discontinued in 2024 across more than 100 locations.

The precision might have been fine for a soft suggestion. “Did you mean a medium combo?” But they built a hard automation. Drive-thru failure isn’t like Netflix failure. You can’t scroll past a wrong order. The customer sees it. The kitchen makes it. Wasted food, frustrated customers, operational chaos. They mismatched the intervention to the precision.

Klarna made the boldest version of this mistake. In 2024, they replaced 700 customer service agents with AI. The CEO bragged publicly that he hadn’t hired a human in a year. By 2025, they were reassigning software engineers to handle customer calls because they couldn’t rehire fast enough. The CEO now says Klarna wants to be “best at offering a human to speak to.”

The pattern is just as consistent on the losing side. Every one of these companies built interventions that were too aggressive for their precision. No fallback. No calibration. No recovery path.

The Frame

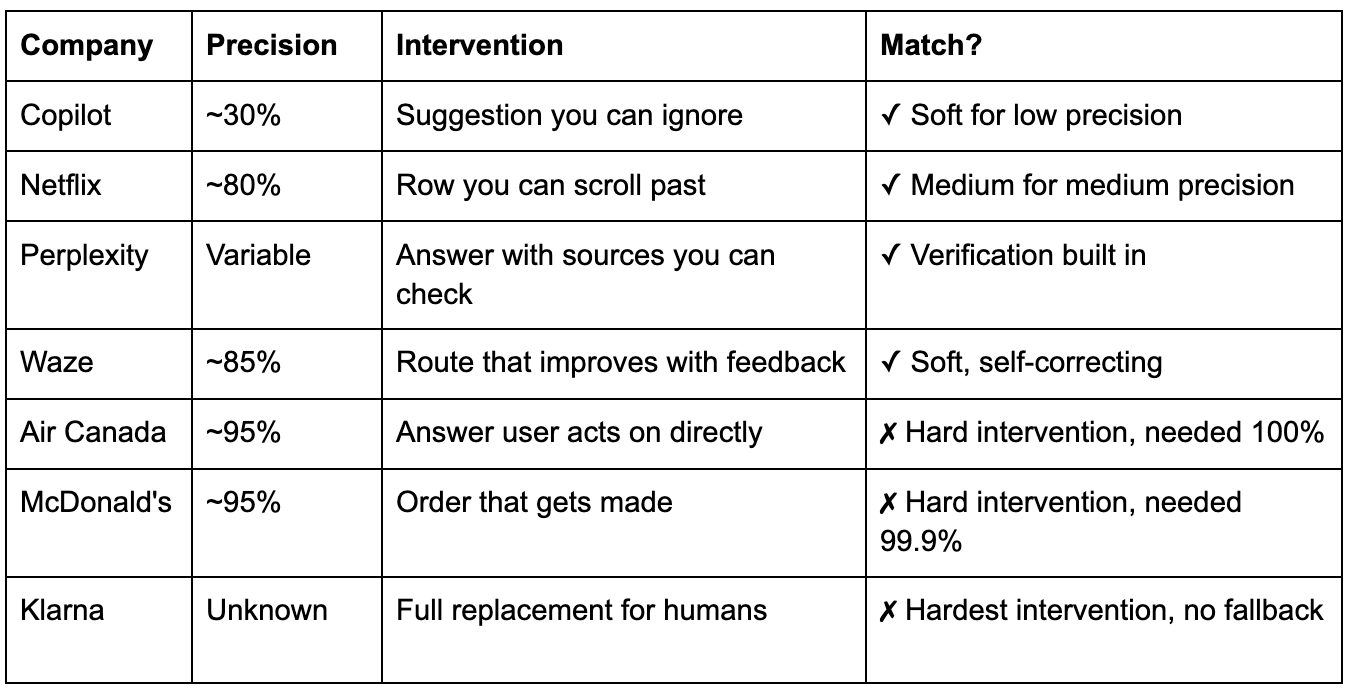

This is the divide:

The precision didn’t determine success. The match between precision and intervention did.

Every winner on this list has a cheap failure mode. Every loser has an expensive one. That’s not an accident. That’s a product decision someone either made deliberately or failed to make at all.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Way back at Booking.com, I had a model that detected the topic of customer service requests. Billing, cancellations, property issues, check-in problems.

The goal was routing. If you know what the customer needs, you send them to the right agent on the first try. No transfers. Transfers are expensive. Every handoff costs time, frustration, and money. A customer who gets transferred once is measurably less satisfied. Transferred twice and you’ve probably lost them. And you’ve wasted time for 3 customer service agents.

So we tuned for high precision. When the model predicted a topic, it had to be right. And it was. But recall was 5%. The model barely fired. Out of every hundred customer requests, it confidently classified about five. The other ninety-five got the same routing they always had.

It sat there, almost perfectly correct and almost perfectly useless. Didn’t move metrics. Couldn’t move metrics. A model that’s right 95% of the time but only makes a prediction 5% of the time has almost no product impact.

Same model. We lowered the precision threshold. Recall jumped to 80%+. Now it caught most incoming requests, but it was wrong more often. Meaningfully wrong.

The old intervention, routing, couldn’t tolerate that. If you send a customer with a billing issue to the cancellation team, you’ve created the exact problem you were trying to solve. The customer gets transferred. They wait again. They’re angrier than when they started. Wrong routing is worse than no routing.

So we changed the intervention.

Instead of routing to an agent, we surfaced self-service options based on the predicted topic. Before the customer ever reached a human. “It looks like you might need help with your cancellation. Here are some options.”

Prediction right? Customer solves it themselves. Never reaches an agent. Cost to serve: near zero.

Prediction wrong? Customer ignores the suggestions, closes the panel, and connects to an agent anyway. No harm done.

30% reduction in contact rates. Same model. Same underlying precision.

The precision didn’t change the outcome. The match between precision and intervention did. We didn’t make the model better. We made the product smarter about how it used the model.

The 70% Mindset

The rare builders share a mental model I call the 70% mindset.

They internalize that the model will be wrong some percentage of the time, and they calibrate the intervention to that percentage. Not hide it. Not wait to fix it. Design for it. They treat the error rate as a first-class input to product design, not as a bug to be squashed before launch.

The simulation they run:

“I have 70% precision. What intervention is appropriate for that?”

NOT “I need 95% precision. How do I get there?”

The difference sounds subtle. It’s not. The first question leads to a product you can ship this quarter. The second leads to a roadmap that never converges.

They start with the constraint. They calibrate inside it.

Gmail Smart Compose works maybe 30% of the time. But it’s explicitly designed not to be authoritative. It’s gray text that disappears as you type. Wrong guesses vanish silently. You never feel wrong. You never feel corrected. The model’s error rate is invisible because the intervention is so soft that failure literally doesn’t exist from the user’s perspective. Soft intervention for low precision. Perfectly calibrated.

Perplexity has variable precision across topics. A question about recent events might be less reliable than a question about established science. But every claim has a numbered source. Wrong answer? One click to verify. They didn’t try to eliminate error. They built verification into the product itself. The intervention assumes the model will be wrong sometimes and gives the user the tool to catch it. That’s calibration.

Waze has roughly 85% precision on surface street timing. But the product isn’t “perfect ETA.” It’s “less traffic.” Wrong prediction? You still arrive. Maybe a few minutes later than expected. And your drive, the actual data from your actual route, makes the next prediction better for everyone. Soft intervention that self-corrects with feedback. The product improves because it ships with imperfect precision, not in spite of it.

This is the mindset shift that separates builders who ship from builders who wait. Stop asking “how do I make the model better?” Start asking “what product can I build with the model I have?”

A startup with 40% precision can beat an incumbent with 95%—if the startup calibrates the intervention correctly and the incumbent doesn’t. This happens more often than you think.

Why Almost Nobody Gets This Right

Nothing in conventional product training develops this skill. And it’s not because training is bad, it’s because the fundamental paradigm changed and the training hasn’t caught up.

Traditional software is deterministic. The spec says X, the engineer builds X, and X either works or it doesn’t. The button either saves the file or it throws an error. The search either returns results or it returns nothing. There’s no “the button saves your file 80% of the time.” You don’t ship that. You fix the bug.

This is how every PM, designer, and engineer has been trained to think. Define the requirement. Build to the requirement. Test against the requirement. Ship when it passes.

AI is probabilistic. The model says X, and X is right some percentage of the time. There is no “fix the bug.” The error rate is the product. The intervention has to match the confidence. “Ship it” isn’t enough. “Ship it with the right calibration” is the actual job, and nothing in the traditional playbook prepares you for that.

The entire pipeline: CS education, PM bootcamps, design programs, agile certifications, produces builders who think in certainties. Then hands them probabilistic tools and expects them to figure it out. Most don’t. They either wait for certainty that will never come, or they ship with certainty they don’t have.

DPD’s chatbot started swearing at customers and writing poems mocking the company after a system update. Disabled immediately. Nobody had asked: “What’s our precision on edge cases, and what intervention is appropriate when the model goes off the rails?” They built a product that assumed the model would behave predictably. The model didn’t. There was no fallback, no graceful degradation, no circuit breaker.

That’s not an AI failure. That’s a calibration failure. The skill that would have prevented it isn’t technical, it’s judgment. Matching intervention intensity to model confidence. Designing the failure state as carefully as the success state.

My team at Booking.com reviews 2,000 to 2,500 applications per year. We hire 3, maybe 5. That’s a 0.2% acceptance rate. As selective as Google, more selective than Y Combinator, 18x more selective than Harvard.

The rare ones don’t have better AI knowledge. They have better calibration instincts. They hear “40% precision” and immediately start designing interventions. Everyone else hears “40% precision” and says “not good enough.” The rare ones ask “good enough for what?” Everyone else asks “how do we get to 95%?”

That’s the gap. And no amount of “AI PM” certifications will close it.

The Calibration Checklist

Before you build anything, answer these six questions:

What’s the precision? Not what you hope for, what you actually have right now. When the model flags something, how often is it right?

What intervention does that precision support? 99% supports hard automation. 80% supports clear suggestions. 40% supports soft nudges. Different precisions demand different intervention intensities.

What happens when it’s wrong? Describe the failure state as vividly as you describe the success state. If you can’t, you don’t understand your product yet.

Who pays the cost of failure? The user? The company? A third party? The answer changes your risk tolerance entirely.

How do you make failure cheap? Soft intervention? Easy reversal? Built-in verification? The best AI products are designed so that being wrong costs almost nothing.

How do you detect failure? For high-stakes decisions, you need individual flags. For low-stakes, aggregate metrics. Match your monitoring to your risk.

If you can answer all six, you might have a product.

If you can only answer the first two, you have a demo.

The Exercise

Here’s how to develop this skill: run the 99/80/40 exercise on your own product.

Take whatever your model does, recommendations, predictions, classifications, generation. Now imagine three scenarios:

99% precision. What would you build? How aggressive would the intervention be? At this level, you can automate hard. You can take action on behalf of the user. You can make decisions that are expensive to reverse.

80% precision. What changes? What do you pull back? At this level, you can suggest confidently. You can surface options prominently. But you need the user in the loop. You need a clear “no thanks” path.

40% precision. What do you build now? Most people say “nothing.” The right answer is almost never nothing. At this level, you can still nudge. You can still surface. You can still learn. The intervention just has to be soft enough that being wrong is invisible.

Then ask yourself: where is my product right now? And is my intervention calibrated to that precision—or am I pushing too hard?

If you’re building a 99%-confidence intervention on an 80%-precision model, you’re building the next Air Canada chatbot. If you’re waiting for 95% precision before shipping anything, you’re leaving the Copilot opportunity on the table. Both mistakes come from the same place: not treating the precision as a design input.

Start with the constraint. Calibrate inside it. Ship.

The Point

You’re not building an AI product.

You’re building a product that has a capability which is right some percentage of the time. That percentage isn’t a limitation, it’s a design constraint. And like every design constraint, it produces better products when you respect it than when you fight it.

The question isn’t “how do I make the model more precise?” The question is “what intervention does this precision support?”

The 99% model and the 40% model aren’t better or worse. They’re different. Different precisions, different interventions, different products. A 40% model with the right intervention beats a 95% model with the wrong one. Every time. Copilot at 30% acceptance rate generates more revenue than McDonald’s AI drive-thru at 95% accuracy. Netflix at 80% relevance saves more money than Air Canada’s chatbot at 95% confidence. The precision doesn’t determine the outcome. The calibration does.

The AI arms race is misunderstood. It’s not about who has the best model. It’s about who matches the intervention to the precision. That’s a product skill, not an AI skill. And it’s the reason the “AI PM” job title is fake. The skill that matters here, calibrating intervention to confidence, is product judgment. It’s design sense. It’s understanding what happens when things go wrong and building for that from day one.

Saying you’re building an “AI product” is like saying you’re building a “C++ product.” The technology is an implementation detail. The market doesn’t care what’s under the hood. Users don’t care what’s under the hood. Your CFO definitely doesn’t care what’s under the hood.

What matters is what the product does.

Lead with that. “20% faster. 30% cheaper. 10x more scale.”

When they ask how, then you say AI.