Growth Machines: The Notion Story

The growth framework that turned near-death into $10B.

In 2015, Notion was dead. Out of money, team laid off, product too confusing for anyone to use.

Ten years later: 100 million users, $10B valuation, and a playbook every founder wants to copy.

The common explanation, “templates went viral”, misses the point. Notion won because they solved a problem most builders ignore: how to make a product get deeper with use, not just wider with distribution.

Most startups chase distribution first: more users, more channels, more reach. Notion did the opposite. They refused to scale until they’d solved a different problem: whether users would do more with the product over time, not just try it once.

That’s the difference between depth and distribution. Depth means users replace other tools, customize their setup, and eventually share what they’ve built, not because you incentivized them, but because the artifact is useful on its own. Distribution just brings people to the door. Depth determines whether they stay.

Notion’s insight: distribution only compounds when depth is already rising. Without depth, growth is just accelerated churn. With it, every new user makes the product stickier for the next.

Here’s how they built that depth, and the framework for knowing when you’re ready to scale.

The first Notion failed on legibility, not ambition

Early Notion was ambitious in exactly the way builders admire. It was flexible, expressive, and theoretically powerful. The problem wasn’t quality; it was interpretation. New users were confronted with too much possibility and too little guidance. The product demanded imagination before it delivered value, which meant only a narrow slice of users could succeed without help. Most didn’t churn because the product disappointed them. They churned because they didn’t know what to do.

Ivan Zhao later reflected on this failure: “We focused too much on what we wanted to bring to the world. We needed to pay attention to what the world wanted from us”[1]. That sentence matters because it reframes the problem. This wasn’t about marketing reach or onboarding polish. It was about legibility, about whether a user could look at the product and immediately recognize how it fit into their life.

The deeper realization came later: “People don’t want to build apps. They don’t think about programming, they simply want something that solves their problems quickly and efficiently”[2]. The first Notion had been built for toolmakers. Toolmakers, it turned out, are rare.

Legibility is a growth constraint, one often ignored. If users can’t see themselves in the product quickly, no amount of distribution fixes that. It only accelerates confusion.

The rebuild was about first value, not feature power

When Notion ran out of money, Ivan Zhao and Simon Last made a brutal calculation. They laid off their entire team of four, sublet their San Francisco office, and moved to Kyoto [3]. Kyoto housing was larger and cheaper, the cost of living was dramatically lower, and they could focus without distraction. In a rented two-story house with paper walls, no heating, and bedrooms separated only by shoji screens, they spent the next year rebuilding everything from scratch [4].

“Neither of us spoke Japanese and nobody there spoke English,” Ivan later said, “so all we did was code in our underwear all day” [5].

The central question wasn’t how to relaunch bigger. It was how to relaunch clearer. What does meaningful value look like in the first hour of use? That question forced a different kind of rebuild. The goal was no longer to showcase flexibility, but to reduce cognitive load. Every interaction was redesigned so the product felt usable before it felt powerful.

During this period, Ivan appeared at the top of Figma’s most active user list, spending 18+ hours a day iterating on the interface [6]. It was a war against ambiguity. As Ivan later put it, “Designers spend too much time on edge cases. Most of the time, what matters is the dumbest path”[7]. In Kyoto, they found that path.

This was Notion’s first major growth decision: scale didn’t matter until first value was obvious.

Templates were not a growth hack

When Notion relaunched, they needed traction fast. Ivan asked early investor Naval Ravikant to wake up at midnight, when Product Hunt’s daily list refreshed, and tweet to his followers to vote. Naval had, in Ivan’s words, “a bazillion Twitter followers” [8]. The gambit worked. Notion hit #1 for the day, week, and month.

But the product they launched wasn’t a blank canvas. It shipped with a set of internally created templates: project trackers, team wikis, meeting notes, reading lists. These templates are often described as a clever growth tactic. That misses the point. Templates were Notion’s solution to the legibility problem.

A blank page asks users to imagine value. A working system demonstrates it. Templates allowed users to start inside something that already worked, rather than designing from scratch. This collapsed time-to-value and removed the need for explanation. Users didn’t have to ask what Notion could be. They could see it operating in a familiar context.

Ivan later described this as “sugar-coated broccoli.” The original vision of letting anyone build their own software tools was the broccoli. Most people don’t want broccoli. But wrap it in something they already care about, like notes, docs, project management, and they’ll consume the underlying capability without resistance [9].

The critical move came next. Notion allowed users to publish and share templates themselves. This turned onboarding into a distributed system. New users increasingly encountered Notion not as a product, but as a solution, as a specific system someone else was already using. They didn’t arrive asking “what is Notion?” They arrived asking “how do I use this?”

Over two years, templates from Notion’s early gallery were downloaded over one million times [10].

Growth became possible once usage became shareable

At this point, Notion’s growth stopped being fragile. A user would customize a template, embed it into their workflow, and eventually share it because the artifact had value on its own. Sharing wasn’t incentivized, it was a byproduct of real work.

This is a crucial inversion. Most products try to engineer virality on top of shallow usage. Notion did the opposite. It engineered deep usage first, then let sharing emerge naturally. That’s why the template ecosystem could exist outside the company. Creators were selling on Gumroad, in newsletters, on YouTube, without collapsing into spam. The artifacts were useful even if you never signed up. Some creators have built entire businesses selling Notion templates, with top sellers earning over $1 million without writing a line of code [11].

Community amplified depth; it didn’t manufacture it

Notion’s community is often cited as the second reason for its growth. That gets causality backward. Community only worked because the product was already embedded in people’s workflows.

Ivan’s early behavior wasn’t a branding exercise. It was product development disguised as customer support. “In the early days, I spent a lot of time replying one-on-one to users on Twitter, making sure they knew there was a human behind Notion,” he explained. “We also logged every piece of feedback we got and tagged it so we could use it to develop features” [12].

When creators like Marie Poulin shared early frustrations with the product’s learning curve, Ivan didn’t just acknowledge the feedback. He watched how they used the product and shipped changes to remove friction [13]. That responsiveness turned critics into evangelists, because users could see their fingerprints on the product.

The results compounded. One ambassador now runs Notion’s subreddit with hundreds of thousands of members. Others built large regional communities in Korea, the Middle East, and Europe [14]. These were power users who became invested enough to build ecosystems around the tool.

Community didn’t create enthusiasm from nothing. It amplified usage density that already existed. Without that depth, community would have been noise.

Why Notion looked slow, and why that was the point

For years, Notion didn’t look impressive by startup standards. There were no viral spikes, no aggressive funnels, no growth-at-all-costs playbook. From the outside, it looked like restraint. Internally, it was discipline.

That discipline came at a cost. While Notion was rebuilding in Kyoto, Coda launched with $60M in funding. Airtable was scaling aggressively into enterprise. Slack had already become a verb. Investors knocked so persistently that Notion eventually moved offices and removed itself from Google listings. Ivan declined most conversations [15].

When Notion finally raised its Series A in 2020, it reached a $2B valuation with roughly 30 employees [16]. That ratio tells you what they were optimizing for: depth, not headcount.

And then that depth nearly broke them. During COVID, as millions of users flooded the platform, Notion’s infrastructure buckled. For years, the entire product ran on a single Postgres instance, upgraded again and again. Eventually, there were no larger machines left. There was a literal doomsday clock counting down to when the database would run out of space and the product would shut down [17].

They froze feature development. Every engineer pivoted to infrastructure. It was, in Ivan’s words, a close call [18].

They survived. And when Notion finally scaled, it did so cleanly because the system underneath could absorb load. Each cohort customized more deeply, relied on the product more centrally, and replaced more tools than the one before.

Notion and the AI Wave: Sticking to core principles.

When Notion launched AI features in February 2023, they faced a strategic choice: build a standalone AI tool, or embed intelligence into the workspace users had already built.

They chose depth over distribution again.

Notion AI is embedded directly into pages, databases, and workflows where users already work [19]. This matters because Notion had spent years getting users to build systems inside the product: project trackers, team wikis, meeting notes, personal dashboards. That accumulated structure became AI’s context layer.

A standalone AI tool knows nothing about your work. Notion AI knows your page relationships, your database schemas, your team’s writing style, your project history. When you ask it to summarize last week’s meetings or draft a document in your company’s voice, it draws on depth that already exists [20].

Ivan described this as “consolidate before you automate” [21]. The years Notion spent getting users to replace fragmented tools with a unified workspace were AI groundwork. The more deeply users embedded their work in Notion, the more valuable AI assistance became, because context compounds.

This is sugar-coated broccoli, version two. The original vision of letting anyone build software tools was hidden inside productivity features people already wanted. The AI vision, giving everyone a reasoning engine for their work, is now hidden inside the workspace they’ve already built. Users don’t adopt “AI.” They just notice that Notion got smarter.

The pattern repeats: depth created the surface area for the next capability to land.

Most companies bolt AI onto shallow products and wonder why adoption stalls. Notion waited until users had built something worth augmenting. That patience is compounding again.

The real lesson: depth earns distribution

Notion’s story collapses into a single growth law:

If the product doesn’t get deeper with use, distribution just buys churn.

Templates, community, and word of mouth worked because users were already doing more with the product over time. Most builders invert this order. They chase reach before depth, then wonder why growth feels fragile. The Notion story is instructive. But stories don’t scale. Frameworks do.

From story to system: the Usage Density Framework

The Notion story collapses into a single constraint:

Growth compounds only when usage deepens faster than reach expands.

Everything that follows exists to help you answer one question honestly:

When a new user shows up, does the product become clearer or more fragile?

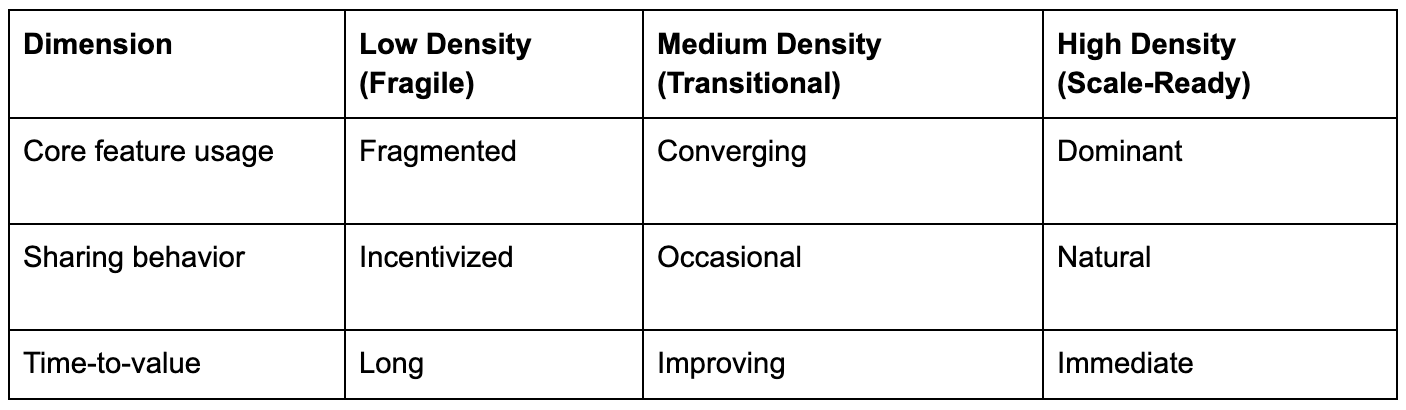

The Usage Density Framework answers that question using two lenses:

A diagnostic (what the system looks like under load)

A depth ladder (why some users become distribution and others become churn)

1. Usage Density Diagnostic

This table is a stress test.

Each row is asking the same underlying question in a different way:

When new users arrive, do they converge toward a clear way of using the product, or do they fragment into edge cases?

If any row is firmly in the Low Density column, scaling acquisition will increase fragility.

Let’s unpack what each dimension actually means in practice.

Core feature usage

Fragmented usage looks like engagement. Users click around, touch many features, and explore the surface area. This often shows up as healthy DAU/MAU, but it’s a false signal. Fragmentation usually means users are uncertain about what the product is for.

Converging usage means retained users increasingly rely on the same subset of functionality. This is the product teaching users its intended shape.

Dominant usage means there is an obvious default mode of use. This becomes the product’s center of gravity.

How to test this

Take your top 20% most active users

Look at which features they use weekly

If you can’t describe a default usage pattern in one sentence, you’re still fragmented

Notion example

Retained users converged on wikis, docs, and project systems, not every block type.

Sharing behavior

This dimension distinguishes earned distribution from forced distribution. Incentivized sharing requires prompts, rewards, or nudges. It scales poorly and degrades trust. Occasional sharing happens when users see value but don’t yet rely on it. Natural sharing happens because the artifact itself is useful. The user shares because it helps them, not you.

How to test this

Look at shares that happen without prompts

Identify what’s being shared (pages, reports, templates)

Ask users why they shared, and if the answer is “because you asked,” it doesn’t count

Notion example

Users shared templates because the template was the value.

Time-to-value

This row tells you how much imagination your product requires. Long time-to-value means users must configure, design, or understand before benefiting. This kills density. Improving means onboarding and defaults are doing some work. Immediate means success is obvious in the first session.

How to test this

Measure time to first meaningful action (not signup)

Watch first-session recordings

Ask: Could someone succeed without reading docs?

Rule

If your product requires explanation before value, don’t scale acquisition.

How to interpret the diagnostic as a whole

You don’t need perfection across all rows.

You do need convergence.

Good growth makes users behave more similarly over time, not less.

If growth increases variance, confusion, or support load, you’re scaling uncertainty.

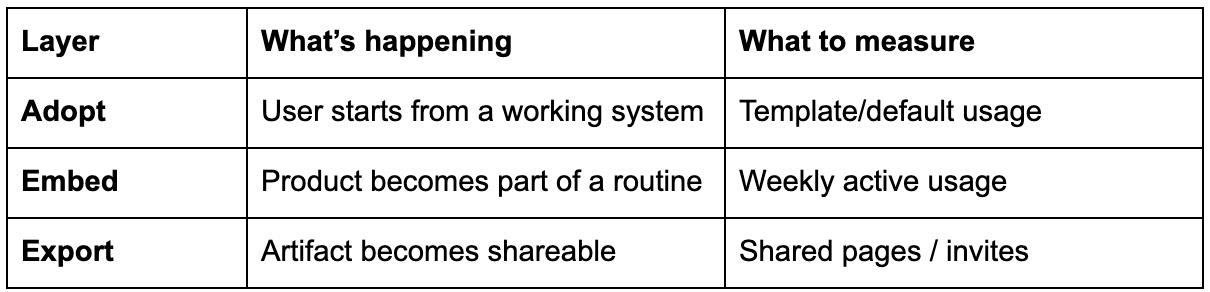

2. The Usage Depth Ladder

The diagnostic tells you whether depth exists. The ladder explains why some users become distribution and others become churn.

Layer 1: Adopt

What it means

The user starts from something that already works. This is where templates, defaults, and opinionated setups matter.

Failure mode

Users start from a blank state and freeze.

What to measure

% of users who start from a default/template

% who complete setup in first session

If users don’t adopt a working system, everything downstream fails.

Layer 2: Embed

What it means

The product becomes part of a recurring routine. Weekly planning. Daily notes. Team updates.

Failure mode

Usage depends on reminders, novelty, or nudges.

What to measure

Weekly active usage

Regular cadence actions

Drop-off when notifications stop

Rule

If usage collapses without reminders, you don’t have embedding.

Layer 3: Export

What it means

The user creates something worth sharing. This is where depth turns into distribution.

Failure mode

Sharing requires incentives or explicit prompts.

What to measure

Shares per retained user

Invites without referral rewards

Artifact reuse by others

Key insight

Export is not virality. It’s proof of depth.

The operating rule (this is the whole point)

Here is the rule that ties both tables together:

You are allowed to scale acquisition only if newer cohorts climb the ladder more reliably than older ones.

If newer cohorts:

adopt less

embed less

export less

then growth is degrading the system.

Stop. Fix depth. Resume later.

Why this matters

Most teams use dashboards to justify growth. These tables exist to prevent premature growth.

They force you to answer one uncomfortable question honestly:

Will more users make this product clearer, or will they expose what’s still broken?

Notion waited until the answer was “clearer.”

That patience is why their growth compounded.

Great write-up, and a great reminder!